The Third Sunrise – Pirin Ultra 160km

It’s approaching 2am on a relatively mild and cloudless September night. I’m halfway down the side of Pirin Peak, the 2554 meter (8400 ft) summit that forms one of the countless climbs on the Pirin Ultra Marathon.

I am almost alone. I can see just one solitary headlamp ahead of me through the dark, perhaps a mile away down the mountain. And I know there is a runner behind me, as I passed him some 15 minutes ago and he’s been bravely trying to keep up. These are the only two other spots of artificial light beneath a star filled sky and an almost full moon.

Descending from a summit is normally something of a rest period in an ultramarathon. Going down is easier than going up. But this is not a regular ultra.

The path, such as it is, offers not groomed trails but a giant bolder field. Huge chunks of granite, often as big as a small car, spread out as far as my headlamp will illuminate.

There are two ways of covering this rocky ground. You could laboriously slide down from one boulder to the next, as if mountain climbing, searching for hand and foot placing. Or you can put your trust in the advanced rubber compound of your trail shoes and the strength in your quads, and leap from one boulder to the next – chancing that grip overcomes gravity.

I am intensively focused in my own world of foot placement and grip, so much so that my mind is empty of extraneous thoughts. It’s like a sort of meditation.

And then the quiet night air is suddenly cleaved by a thud and the most almighty scream from about 100 metres behind me. I turn around and without thinking, start hauling myself back up the rocks which I’d hoped to have put behind me for life – back towards the source of the sound.

I can see a runner slumped over back up the mountain. As I climb, as fast as I can, my heart rate rises, thinking through the possibilities. I start to consider that an extraction of an injured runner from this boulder field is more than a one person job. More than I can manage.

I reach the runner whose headlamp is illuminating his right ankle and the blood oozing from his lower shin. My headlamp quickly darts around, searching for the source of his pain. Two headlamps on a lonely mountain.

His exhales are slow and parsed through what sounds like a Bulgarian expletive, over and over. My breathing is fast and shallow as I try to overcome my sudden exertion. It’s not Sleepless in Seattle but Breathless in Bulgaria.

I feel around his ankle searching for any protruding bones. I assume he’s broken his ankle. He speaks no English. I speak no Bulgarian. But the power of his scream says “broken bone” in any language.

The front of his shin looks as if it has had an encounter with a cheese grater, but his ankle looks mercifully intact. Or at least still joined to his leg.

As I check him over for any other broken bones or gashes, his breathing slows and the yelled expletives give way to a quiet, delicate and pitiful sob. It’s a sound you don’t expect from a big Bulgarian man that looks like this.

My sleep-deprived brain is discombobulated and unable to make the code-switch from looking to provide physical assistance to emotional help.

In the normal world, such a broken, sorrowful sob would demand putting your arms around someone and giving them a big comforting hug. But giving a big Bulgarian man I don’t know a hug on the side of a mountain seems just a bit too weird.

I tried to offer some soothing words.

“I think the path smooths out just down there”. But of course this was not true.

Perhaps he senses my awkwardness through his crying and he brushes away my enquiries with a wave of his hand. He just wants to be left alone, left in his own world of sorrow.

His bones may not have been broken but is soul was well and truly crushed. He didn’t need airlifting out. But he might have needed a psychotherapist flying in.

There wasn’t really anything more I could do. So I turned and continued my route down. I didn’t catch his race number or his name, so I’ve no idea if he made a magical recovery and finished the race, or if he’s still wailing uncontrollably on a psychiatrists couch somewhere.

This is the Pirin Ultra. And it’s not for cry babies

Path to Pirin

Bulgaria hadn’t been much on my radar. And certainly not for mountain running. But it turns out that Bulgaria has some wonderfully rugged high mountains – the Pirin Mountains – which become a mecca for winter sports in the season. Or perhaps that should be ‘became’ a mecca for winter sports. For here too, climate change is starting to wipe out the snow and hence the winter tourism season. Last year’s winter was even too warm for the artificial snow machines around the main town of Bansko to do their energy intensive business.

Ironically enough, the reason I was in Bulgaria for a race was because I had failed to finish another race a couple of months earlier. For me, my path to the Pirin Mountains began on the side of a mountain in Colorado on the Hardrock Hundred Endurance Run, where I too had started to lose my mind.

I was about 90 miles and 44 hours into Hardrock, when the sleep demons finally caught up to me.

Through the early part of the race I’d been slower than planned and had so little buffer against the cutoff times that I’d had not a minute to sleep. I was running without a pacer, who might have been able to slap me around the face and tell me to get myself together.

I was painfully desperate for just a few minutes of a restorative nap, but simply didn’t have the time.

Obnoxious Knees

Hallucinations are common in ultra marathons, particularly those that keep runners awake for multiple nights. And they were something I’d experienced before.

On one of my first big ultramarathons, I’d developed a stress fracture in my right shin and torn a knee meniscus in my left knee. Rather than pull out, I’d pushed myself to the limit – or possibly quite beyond it, to finish.

Because of my injuries and slow progress, I had no time to sleep. On the second night of hobbling through that formative race, the sleep deprivation manifested itself in a delusion where my knees, screaming with pain, started to answer back to the insults I was directing their way.

Presumably growing tired of the insults, my knees eventually started to answer back. And taking things just a bit too far, they then started to consult with each other about my shortcomings as a runner, and general poor character as a human. When your knees start talking about you in the third person, you really are in trouble. Having my own knees talking trash about me to each other clearly did little for my mood.

By contrast, at Hardrock the hallucinations were more tame, and I had simply lost the ability to follow the course markers. In the middle of the night, and on the final climb of the race, the reflective markers were generally visible for a few hundred feet up the mountain. And if that wasn’t enough I had a simple line displayed on my watch that showed a graphical representation of the course. I was so close to the finish. All I really had to do was keep the dot representing myself on my gps, on the line representing the course, and I wouldn’t get lost. And yet somehow I did.

On the final climb, I remember bending down in the darkness to look at the course markers and studying them as if they were some sort of unique flower, and not quite understanding what they were for or even quite what I was for.

On the way up that final climb of the race, the warning signs had started to appear. I’d sat down on a rock, having just emerged from an Estate Agents. I’d been convinced that there was an elevator in the side of the rock that I needed to find. And perhaps that I was on totally the wrong mountain. I asked two passing Pandas if they could kindly direct me towards the Hardrock course. They were two runners who’d I’d spoken to just a couple of hours earlier.

“Just keep going up, Owen” one of them replied.

“But then how will I get down?” I wondered, possibly to myself, possibly out loud.

I can’t really remember much of what happened over the next hour. Nothing much made sense. Those watching my satellite tracker say they could just see me veering wildly across the side of a mountain. Thinking back now I can remember little more of it than a dream.

All I remember is that as my mental faculties started to come back and I started to push on towards the finish I’d lost too much time with Pandas and Estate Agents.

Despite running as fast as my tired legs could muster, by the time I reached the finished line in Silverton I was nearly an hour over the 48 hour cut off time, so wasn’t an official finisher in the race.

All About Hardrock

For a certain kind of ultra runner – me included – running Hardrock is the highlight of a lifetime. It’s hard to get a place in this epic race in Colorado. Thousands apply for just 150 places.

Finishing Hardrock gets you a place in the lottery for next year’s race. And strangely enough I’d still wanted the chance to keep coming back and run the race again.

There are just a few other races around the world that the organisers think are also sufficiently challenging to demonstrate your preparedness as a would-be runner for Hardrock. These qualifying races too get you a chance to enter the lottery.

Immediately after failing at Hardrock, I’d begun to wonder whether this might be a sign that my time suffering through ultramarathons – particularly the more challenging races – might be coming to an end. Maybe Hardrock 2024 might be an appropriate swan-song. I’d finished the race the race of my dreams once and failed once. Did I really want to commit to more endless suffering. Perhaps this was a sign that it was time to move on.

In any event, I thought I’d have to wait until next year to find and then train for another Hardrock qualifier. I’d miss the lottery this year – something I’d not done for years. I’d take the rest of the year off, enjoy myself, and then start training again in the new year and put it out of my mind until then.

Go Now

I’m not really sure when the realisation came that training back up to Hardrock fitness becomes increasingly difficult with age. I tend to run one big race in the summer each year, then take the rest of the year off from the rigours of training.

But maybe it would just be easier to get a Hardrock qualifier whilst I was still almost Hardrock-fit. It would be easier to maintain the fitness than let it go and try and regain it.

As I flew back from Colorado to London, I looked through the list of qualifying races in the autum. It looked like there was a race in Japan, one in Cape Town, another in Switzerland, Australia and Bulgaria.

But most were either full, just missed the Hardrock lottery deadline, or were a huge logistical challenge to get to.

Bulgaria seemed my last chance to get back in the Hardrock game.

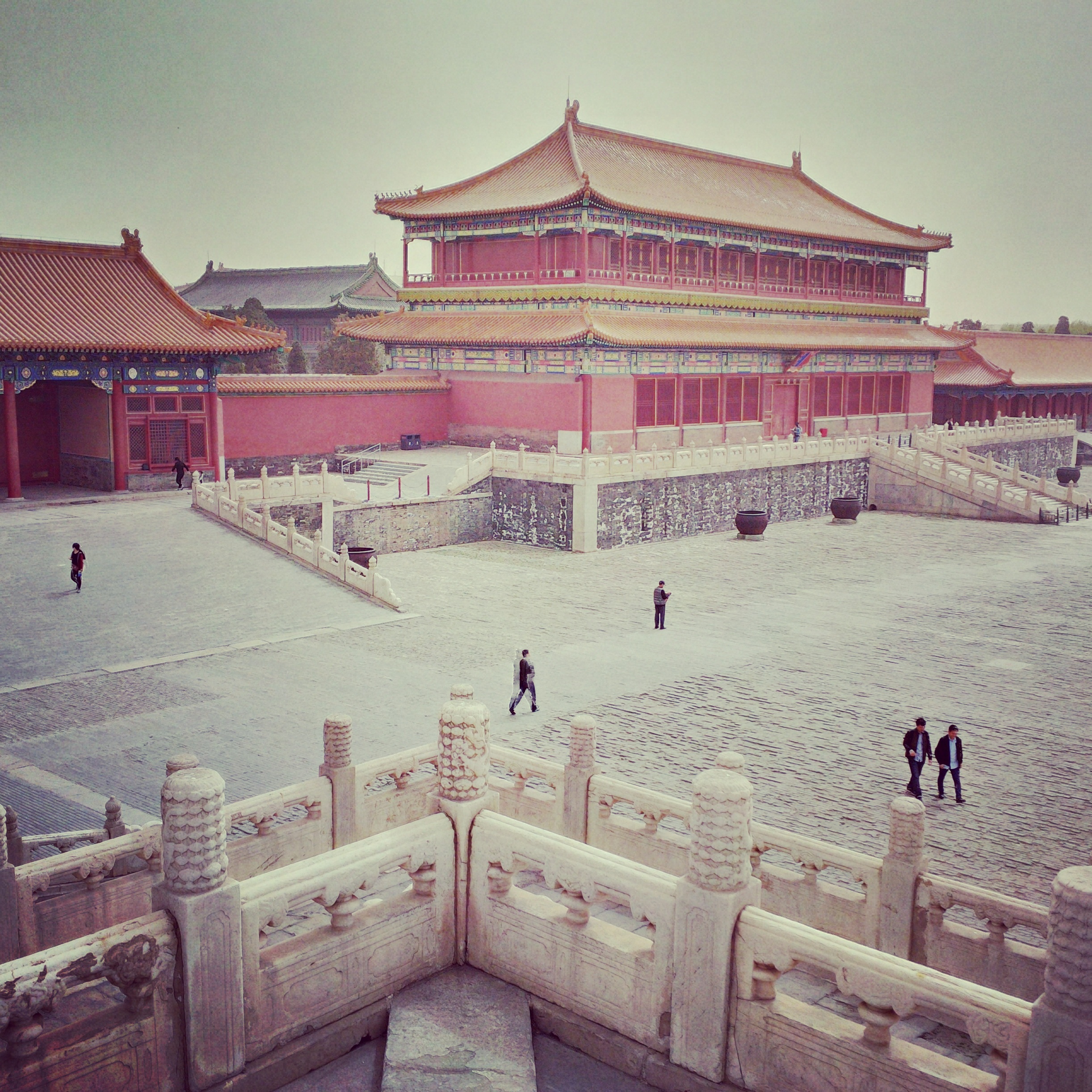

Only just over two months after Hardrock, the blisters had barely healed but I was on a late night flight to Sofia. And then on to a rickety old soviet train to Bansko in the heart of the Pirin Mountains.

![]()

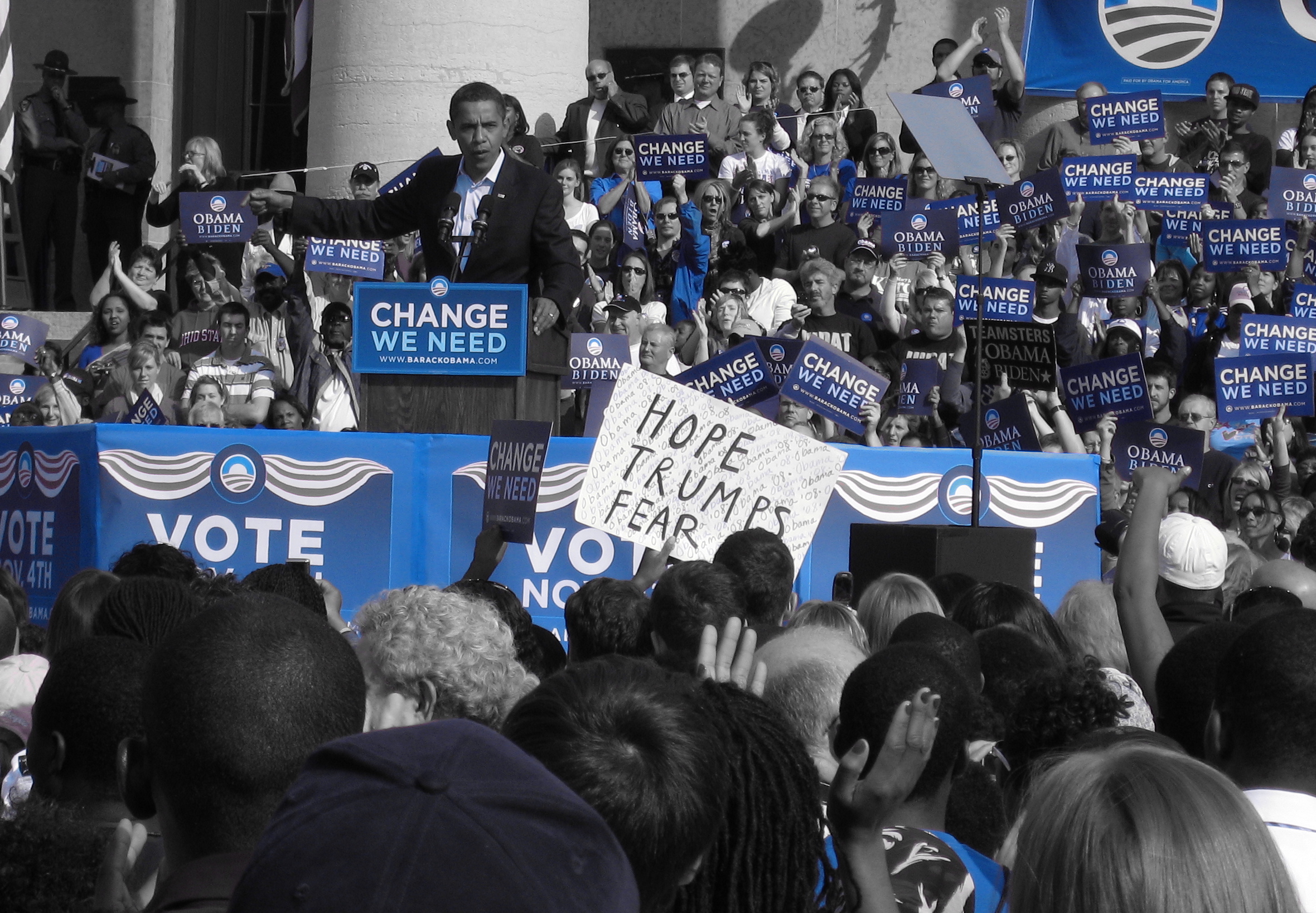

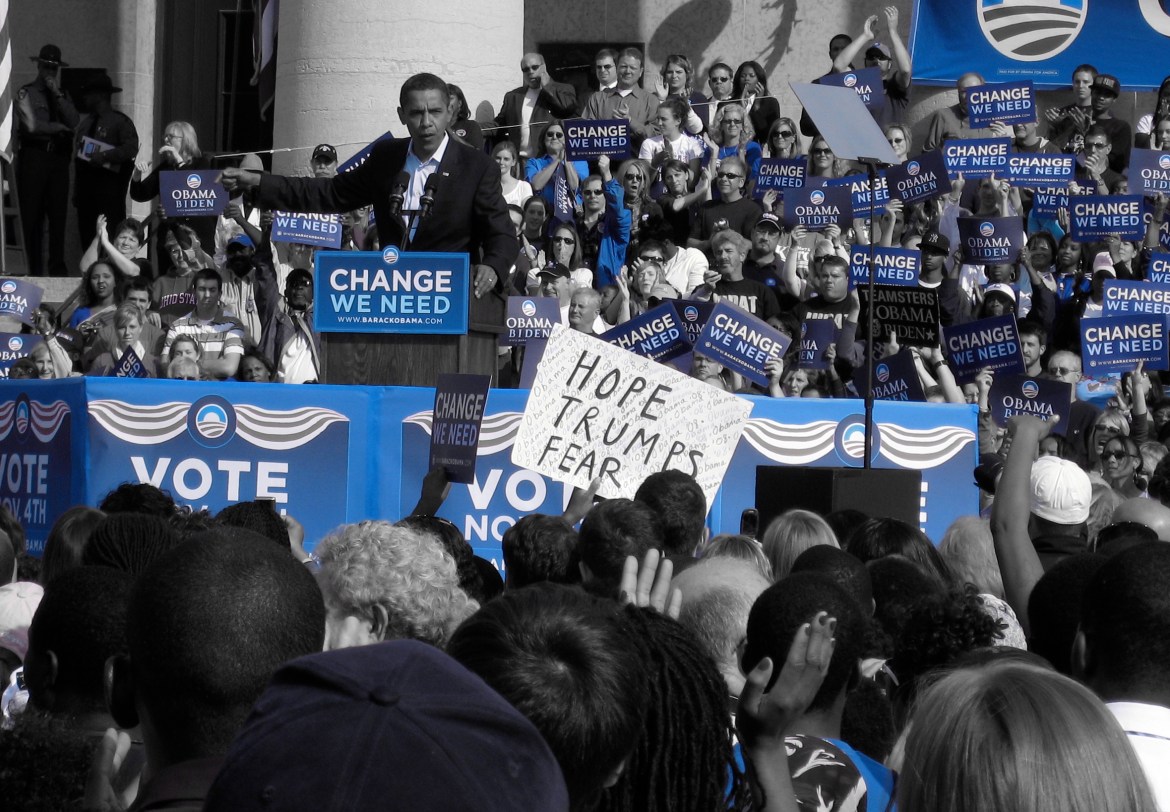

![]()

Show me the info

There was however a distinct lack of information about the race available online. After Hardrock this low-key race appealed. Hardrock had been writing to me for months in the lead up to the race.

Look up any of the big races online and there are an abundance of race reports and YouTube videos available. But there’s relatively little out there about the Pirin Ultra, and even less that’s not in Bulgarian.

There were about 100 people signed-up for the race when I eventually made the decision to enter.

There were a smattering of other international runners on the start list. Three Brits, a Dutchman, some Norwegians, a few Poles, an American and a sprinkling of runners from Bulgaria’s direct neighbours – Greece, North Macedonia, Romania.

I dare say that most of us had looked up the starting list before travelling to see who the international runners were. I’d guessed that most of them were, like me, going largely for the Hardrock qualifier.

Within the small group of ultra marathon runners there is an even smaller group who enjoy travel enough fly to one of the more extreme races with the sole objective of finishing just so they’d be able to enter the lottery for another race.

Booking

When signing up for the race (just €80), the organisers offer the opportunity, for a small extra cost, to be booked into an (unspecified) race hotel and have a pickup transfer from Sofia airport (at an unspecified time).

In addition to the 160 km race, there were a number of shorter races organised at the same time, as part of the Sky Running series. The website said these races would take place between 21st and 23rd September – but gave no information about when each race would start. There was just a note that the race schedule would be published 10 days before the race.

It later turned out that the airport pickup to Bansko would be exclusively on Friday with a return to Sofia on the Monday.

I’d already booked my flights and I didn’t really fancy turning up in Bansko late on Friday night for a 6am start the next day. Nor finishing the race on Monday morning and having to be bundled into a bus on Monday afternoon back to Sofia. So in the end, despite paying for the transfer, I ended up sorting out my own transport too and from Bansko.

I’d also booked and paid for two nights in the race hotel – assuming one night before the race and one after. But it turned out that these nights could only be on Friday night – the night before the race. And Saturday night – one of the nights I’d be out on the course. Bonkers!

In the end despite paying for the race hotel, I just decided to book my own accommodation elsewhere. At a hotel with room service and a sauna.

The contrast with Hardrock could not be starker. At Hardrock I’d been receiving weekly emails in the months coming up to the race. Other people I spoke to at Pirin had said that they’d emailed the race director with various questions, and not had a reply.

I was fairly relaxed about the lack of communication. In the end I thought my flights were cheap and the hotels even cheaper. I’d not had to invest massively in the race. If I needed to book another night or another flight, then so be it. Embrace the unknown.

I’d also assumed that the race director was deliberately trying to channel Lazarus Lake, the organiser of the Barkley Marathons by refusing to provide helpful information. In a race like the Pirin Ultra you need to be comfortable with ambiguity. Comfortable not having a marked course. Comfortable being self sufficient with food. Or at least, if not comfortable, then at least happy being uncomfortable.

There were few rules for the race. But one that stood out – “no whining”. Don’t expect too much and you won’t be disappointed. And for €80, what can you expect.

The Unknown.

What is known about the Pirin Ultra is that it’s supposed to be a 160km long race, with more than 11,000 metres of climbing. And you have 50 hours in which to finish. About ten days before the race, the timetable was published, showing that the race was to start at 6am on the Saturday morning. Meaning you need to finish by 8am on Monday morning.

The course is supposed to be completely unmarked. Although it turns out they’d marked one small section across a boulder field. And another small part of the course that follows the route of the 66km race which starts a day later, but is a fully marked.

Although not explicitly stated anywhere, the course profile seemed to show a drop bag icon at one aid station that you reach at 26km and again at 86km.

I checked in for the race on the Friday afternoon along with some racers for the shorter distances. After a mandatory kit check I was given my race number and told I could collect my tracker on Saturday morning, before the race. I handed in a big drop bag, which I was unsure if I’d ever see again. In it were a couple of AirTags, so at least i might have a chance of knowing where it was afterwards.

Later that afternoon there was a streamed ‘e-briefing’ for the race, which provided a little bit more information.

And then in the evening there was a pre-race dinner that had been included for the international runners staying at the hotel.

The race director did a quick tour of the dining room, and I asked him about the course. He seemed like a really nice chilled guy.

Hardrock is known for its numerous river and stream crossing – so much so that your feet are almost constantly wet. I asked the RD if that was the case for Pirin? He said it had been dry for weeks and there was very little water on the course – so make sure you carry enough to drink. There are long distances between aid stations.

I also asked about the finisher rate, thinking it was somewhere around 50%. He said most years about 30% of the 160km race finish. He seemed to take genuine pride that this was much lower than Hardrock. It also seemed to add to the narrative that things could be made easier for runners – but wasn’t the point for it to be difficult?

The info about the water and finisher rate were the most useful bits of information I’d received. Starting a race where 70% of the field might quit does help to set your expectations.

Race Day

We had been told to be at the start line for 5:30am the next morning to receive our race trackers. It wasn’t like there were many of us to process, so I wasn’t too worried about long queues.

None of the international runners knew each other before the race but we started emerging from hotels across town in what felt like the middle of the night, and congregated on route to the town square. It’s easy to spot a foreign ultra runner.

On leaving the hotel, I bumped into a couple from Essex, one of whom was returning to the race after her DNF a few years ago.

Most were here for the Hardrock qualifier, and many to settle old scores of a DNF at Pirin from years before. We each shared stories of how little information there was about the race online. Perhaps that was part of the charm for most of us.

Come race morning there were 111 people on the starting list for the 160km race, but only 87 people had turned up to register. That’s already a high drop out rate. Is a DNS better than a DNF?

That number makes even the tiny starting line for Hardrock seem positively crowded. My local Parkrun is much bigger than this.

And at Hardrock you’re allowed a pacer out on the course. No such help at Pirin. It really would be lonely out there.

First Sunrise

Sunrise was officially just after 7am in Bansko at this time of year. So twilight would begin around 6:30. But beneath the dense canopy of the trees it would seem darker for much longer.

The sky was pitch black when the race director started the count down.

The starting arch straddles some steps in the town square, which has the effect of at least slowing down the runners as they head out into the mountains.

The starting gun went off and we set off up the gentle slope of Bansko’s streets, and then off the roads and onto dirt trails through the trees.

There isn’t much to say about those first few kilometres. We headed up snow-free ski trails and then off through the woods.

Early on I started chatting to a Dutch guy who was back to settle a DNF from last year. (Sadly he didn’t finish again this year).

I’d started trying to nibble a pack of crisps to keep my energy levels up. And I’d managed to get through quite a bit of water.

The first aid station came at the small Bandaritsa mountain hut 11km in. I was gagging for a coffee but there was no hot water. I made do with a coke, which was at least flowing freely. I filled up one of my water bottles with Coke for the journey ahead. At least some sugar and caffeine would come with me.

But as I started to survey the other food offerings I knew I was going to be sick.

Behind the hut I puked up a pathetic thick beige paste of chewed crisps. As I wretched from deeper in my abdomen, I remember thinking that at least the water wasn’t coming back up, so I wouldn’t be getting dehydrated. I covered the embarrassing beige lump with some leaves – embarrassed to be puking quite so early. But also embarrassed at how pathetic my puke was.

There was a time when nausea and puking would dominate my races. Now it was little more than a stomach reset.

I rinsed my mouth with water and downed some the coke. It stayed down for a bit. I was still feeling good.

As the sun rose over the peaks it became a perfect day. Not too hot. No wind. But gloriously clear blue skies. You could not ask for better weather.

Mandrata

I continued trying to eat some chocolate Twix biscuits and sip on the coke. Every now and again my stomach would try and puke up a bit. And I’d teach it a lesson buy forcing down more food. It felt like trying to get a rebellious child to eat its vegetables. ‘You’re going to keep eating this until it stays down’

At the Mandrata aid station, at kilometre 26, we first got access to a drop bag, which we’d also have access to again after the first loop when we returned 86kms into the race. I was a little surprised to see the drop bag had arrived at the aid station. All the bags looked the same, having been wrapped in bin bags. And they didn’t seem to have been placed in numerical order. Chaos! My AirTag helped me find my bag pretty quickly.

I’d packed some spare shoes and socks – which I’d keep for my return later. No point changing shoes quite so early on. The RD was right, the course was bone dry. I’d also packed a couple of pots of instant mash potato. But of course there was no hot water to mix it with. Another drought.

Contemplating forcing down a pot of cold stodgy mash potato, the Dutch guy saw my potential plight and offered some hot water from the massive thermos flask he’d packed in his drop bag. He’d clearly done the race before and knew what was missing.

I thought I’d be taking a risk eating the whole pot of mash in one go, and assumed I’d be leaving another beige paste just a bit further up the trail. But the hot food instantly settled my stomach and I think the 5 or 6 times I’d been sick up until then were the last.

Route finding was sometimes easy and sometimes more difficult. Occasionally you’d have to push through a dense clump of pines, or cross, then cross back over a stream. But in the open air the course finding wasn’t too challenging.

But having the map feature enabled permanently on your watch really does zap its battery. So it’s important to keep thinking about whether it’s sufficiently charged as much as whether you are.

The huge design flaw in Garmin watches is that you can’t charge them whilst wearing them, so you have to carry them in your hand with a battery pack whilst you run. And you can’t do that whilst you’re climbing hand-over-hand up a rock face. I wasn’t ever at an aid station long enough, and in any case they were too far apart, to get enough charge from them alone. And I’d known from past experience that you didn’t want to get into a situation where your watch needed charging just as a storm or difficult climb was approaching.

On an unmarked course, keeping watches, phones, satellite trackers and headlamps charged takes some planning. Much like managing your own energy reserves. When your battery starts to reach empty, you’ve left it too late.

After the first entrance into the mountains, the course is essentially made up of two big loops, which connect at the centre – at Mandrata – like a giant lopsided figure of eight.

The first loop features a section of mountain highlighted in red on the course profile. In a howling wind or rain storm it wouldn’t be pleasant but I didn’t feel at all exposed on this mild September night.

There was a fair bit of scrambling, pushing through vegetation which cut up my lower legs, or patches of stinging nettles, but not much exposure.

The aid stations are far apart. Particularly when moving quite so slowly over the terrain. Sometimes seven or eight hours between aid stations. So you need to be fairly self-supported with food. It wasn’t amazingly hot, but I had to stop a couple of times to filter water and fill up my water bottles from the few streams. There were a lot of animals on the course, so drinking straight from the stream probably wouldn’t be senseable.

It was on the descent from Pirin Peak, on the first night, about 55km in that I encountered my crying Bulgarian man. Further down the course we – though perhaps not him – were back into a wooded pine forest.

Trying to track a faint path through the woods was hard work. Particularly at night in some of the tighter valleys and with a dense forest canopy above, it was hard to get a reliable gps signal, and to know whether the path was 10 metres to your left or right. Often you’d just end up bush-whacking through the forest, climbing over broken branches and tree stumps – tracking parallel to a path but not knowing quite where it was.

There is an epic race video online, with an awesome looking ridge. But there’s so little information online about the race, that it wasn’t clear to me that the ridge-running only forms part of the shorter 38km Sky Running race. I suppose it wouldn’t be hugely sensible to send fatigued 100 mile runners that way. But I was a bit disappointed not to get the really technical scramble and Via Ferrata.

Speaking to other runners who’d done – or part done – the course before, I found reassurance that the first loop was where most of the technical climbing was.

Second Sunrise

I’d run with a Dutch guy for a bit at the beginning of the race. And with a Bulgarian woman for a while, and then an Israeli guy. But large parts of the course I was out by myself.

Whilst running with a course on your watch, it’s hard to have a full overview of where you are on the course. Your scale is zoomed down to the your immediate vicinity. You have no real idea where you are in the field – how many people are behind you and how many ahead.

Our race numbers had an elevation plot of the course on them, with indications of mileage and elevation gain. But there was no overview of the course outline.

I had diligently printed out and laminated the cut off times. But this was stashed in my backpack.

It was on the descent back to the aid station at the centre of the two loops, Mandrata at 86km, with our drop bags, that I began to worry, and then be sure that I was going to miss the cut off.

I had it in my head that the cut off time at the Mandrata aid station was 5:30am on Sunday – some 23hours 30 minutes after starting. Over the preceding hours I’d grown increasingly concerned, and kept pushing my pace. I considered stopping to fish out the timing chart to double check, but assumed that would waste more time. And in any event I couldn’t really run much faster, so even if I had it confirmed it wouldn’t make much difference.

First my watch rolled over to 4am. Then 4:30. It got closer to 5am and I was still jogging on at what I felt was a fair trot. 5:15am and I clenched – this seemed like I was going to be out of the race. I was still a fair way off the aid station. 5:27 … 5:28 it wasn’t close. I was going to miss the cut off.

My thoughts switched to my hotel room. It was one of the nicer hotels in Bansko. Recently renovated. Expansive, crisp, white Egyptian cotton sheets lay waiting for me. A lovely bath room. And a spa complex.

I’d been feeling pretty sleepy during the first night section and was starting to relish the opportunity to crawl into bed.

I knew it would take some time to get back from the aid station, as it was the other side of the mountains from Bansko. But I figured I’d be able to grab a quick nap in the aid station before being taken back.

I’d had a blast doing the 86kms. I wasn’t particularly beaten up by the course. Rather than being disappointed, I was actually rather pleased to have another free day in Bansko.

So I was in buoyant mood when I finally arrived at the aid station just before 7am. It was still pretty dark in the forest. The aid station had moved inside the hut. It was pretty cramped and dark inside there too. But warm. Gloriously warm.

There were a spread of perhaps 5 other runners sprawled out inside the hut. All looking pretty dishevelled. A couple with head in hands. A few laid out trying to sleep.

So when I entered the hut and announced in a chippy, upbeat tone to everyone and no one in particular

“Oh, so have we all missed the cut off?” there was a minor commotion as runners quickly stirred.

“No – there’s no cut off here”, the sole volunteer announced.

“What, really?” I said in a slightly less upbeat tone. Dreams of my bed and steam room rapidly disappearing from my mind as a dream is forgotten on waking up.

So I have to carry on?

I set about plugging in various devices to charge. Swapping over headlamp batteries. Changing shoes, washing feet,

I went outside to brush my teeth and tongue.

As I was brushing and trying not to gag, a runner left the hut and said in an american accent

“I’ve just done the same thing. Feels amazing doesn’t it? If it’s good enough for Courtney…”

Brushing your feel and wiping your race really does transform how you’re feeling.

As Courtney says “Look good, feel good, safety third”

I tried to get some hot water for my mash potato, but there wasn’t any. Nor any coffee.

Instead a got a bit of a lecture from the volunteer about how bad my artificial dehydrated food was, and got offered some slightly tepid soup. It didn’t really hit the spot. I left the mash behind.

I figured I didn’t really have time to sleep so I left the aid station and immediately struggled to follow the path. We were deep in a valley and again with heavy tree coverage.

Was the path to the left or the right of the river. I just couldn’t figure it out. “Get a grip, Owen”

In the mountains the sunrise is never particularly pronounced if you’re not on a summit. It just starts to lift the gloom.

I caught up with the american runner and we chatted for a bit, until he said he needed to get 10 minute sleep.

I think I must have a soporific effect on people. Maybe that’s why I feel so tired in races – it’s the sound of my own internal monologue sending me to sleep.

I eventually caught up two Polish runners as we nearly summited peak. The ground was hard with frost and the sky again brilliantly blue. How lucky we were with the weather.

We passed a little mountain hut with hikers looking like they were preparing to start the day.

It was early. We assumed the hut was closed, but I thought we’d just give the door a push to check.

It was open and somehow pushing through that door was like entering into a magical wonderland. We managed to order coffee – which one of the Polish guys treated me too. (Bring small denomination notes with you – I just had the equivalent of a £20 Bulgarian LEV note and a credit card – neither of which they seemed inclined to take)

It was unbelievably wonderful inside. It was like an Edward Hopper painting made real. With the added advantage of the smell of coffee. The sunlight streamed in and the mountains looked picture postcard perfect through the windows. If they’d had the Sunday Newspapers, I’d truly have thought I’d died and gone to heaven.

I knocked back the espresso and was ready to leave, when I noticed the Polish guys checking out the breakfast menu. If I sat, I’d never leave. I left them too it and headed out into the cold but brilliantly clear morning.

The day passed relatively painlessly. Large parts of the day were spent on the course of the 66km route, which at least gave other people to chat to, and the short-lived luxury of a marked course. The 66km race started early on the Sunday and tracks part of the same course as the 160km race.

I stripped off down to my shorts and washed in one of the faster flowing streams. Cooling off and getting the grime off you comes second only to brushing your teeth in terms of a restorative effect.

I thought I was getting a few odd looks and double takes. But it seemed a perfectly sensible thing to do.

Normally in a long race I’ll put plaster over my nipples to avoid any unpleasant chafing. You only have to see one bloodied shirt in a marathon to remember to never make that mistake.

Anyway, I’d forgotten to bring any really adhesive plasters with me, so on race morning I got creative and had the clever thought to use some KT tape – the luminous blue stretchy and super adhesive bandage that you sometimes see athletes use on their legs – for the same protective effect. It was only later that I realised that seeing a man with blue luminous nipples emerging from the river must have looked a bit odd. Or a bit statement making.

I’m not quite sure when the american guy caught up with me again. But our paces seemed in sync and we buddied up as the sun set for the second night. We passed a few other runners, and a couple of runners passed us.

Eventually in the middle of the night the course for the 66km and 160km races parted in the night. Suddenly we runners on the long course cut a much lonelier affair. I was glad of the company.

Again there was a fair amount of scaling over boulders. And long scrambles on all fours as we made for each summit.

Both of us were clearly trying to work out pacing and times. I’d figured that we needed to be at the last aid station by midnight – to give us eight hours to cover the last 26km of the course to the finish.

But for both of us the wheels started to come off. For him he managed to bash his knee on one of the rocks and was seriously concerned about the sharp pain emanating from deep within his knee.

For me, I was starting to get a deep sense of deja-vu. And also slightly conscious that I was beginning to get a weird perception that we were going around in circles – despite clearly being on the track on the gps trail on my watch. This is what started to go wrong in Hardrock.

With two other runners we struggled we passed a giant lake and then climbed the boulder field over the last really big climb. But all four of us struggled to find the route over the saddle. All for of us looking in different directions.

“Get a grip, Owen. This is where you get timed out”

Over the saddle and the path was fairly distinct now – compacted mud in places speckled with white rocks of varying size which reflected off my headlamp.

But somehow these weren’t rocks but discarded cups and saucers, and plates and the a guitar.

When I get really tired my powers of logical reasoning start to break down. And Occham’s razor – that the simplest explanation is the most likely goes out of the window.

Rather than “they’re rocks” my brain started to create an elaborate story around why companies had disposed of bone white china on the path.

Later the china gave way to guitars and a washing machines. Oh maybe I could do a spot of washing whilst we’re up here.

My american friend was slowing a little and worried about taking any more pain killers. He urged me to go on alone. I was tempted. But also quite enjoying the company and the varied chat. He’d paced Hardrock a couple of times.

And also perhaps I was a little conscious that I’d failed at Hardrock because I’d lost the ability to follow a a simple line on my gps. If I was already starting to walk on crockery, perhaps a second pair of eyes would help. Maybe he was the pacer I’d never had at Hardrock.

He was still talking of dropping at the aid station, so I prepared that I’d have to go it alone from there.

In my head I’d already been timed out once that day, so wasn’t particularly panicking if I got timed out again. I was almost expecting not to finish.

Both of our senses must have been going a bit off as we both thought we could see an aid station through the dark – but much higher up than us. Which was odd as we knew the profile of the course meant we needed to descend to the final aid station.

I’d been fighting off a strange sense of deja-vu and somehow was still a bit confused at the prospect of following a simple line on my gps.

I remember saying – as if it had been drilled into me post Hardrock – that my watch still showed we were on the course so we must continue. I was talking out loud – but to myself.

Sensing the aid station or at least my increasing confusion, my american friend led the way for a bit and we eventually found what looked like a large semi-deserted mountain hut.

I still wasn’t quite convinced it was the aid station – but once inside there were three cheery volunteers who welcomed us. There was scant little left in terms of food or drink. No coffee. No hot water.

In my head I’d calculated that we’d need to have arrived at the last aid station by midnight in order to have a decent chance of making it to the finish some 26km further on, in time for the final 50 hour cut off at 8am.

It was now just about 2am. But the volunteers were bright and optimistic and told us that the course was now fairly groomed flat trail – or heaven forbid – proper roads. So we’d be able to make it if we pushed. We were ahead of the cut off time at the aid station. And I’ve never voluntarily pulled myself from a race.

We looked at each other and decided we’d make it. The volunteers loved our optimism. Most runners they’d said had been pretty grumpy coming in. We were buzzing.

We stuck some KT tape on my friends knee. And some cooling get. I think he popped another pain killer.

Those final hours of an ultramarathon when you’re up against it with a hard cut off are supposed to be an awful slog. But I can’t pretend they were. I certainly enjoyed the run wards the finish.

At one point, I picked up a rock so convinced it was a small espresso cup. It wasn’t. I clearly needed sleep.

Once when we were both struggling with tiredness we lay down on the track for five minutes to try and get some sleep.

My nausea had stopped long ago, but my running buddied had to stop a few times to fend of nausea.

We ran as much of the flatter and downhill sections as we could. And power hiked the uphills. All the time paying obsessive attention to our pace.

Soon the pitch black of night made way to the gloom of an early morning in the mountains.

As we got closer to town the murky morning mist gave way to a brilliantly clear cloudless sky.

All the time we were checking our watches. Maybe we’d finish with 40 minutes to spare. Now maybe 30 minutes. Ok perhaps we’d finish with 20 minutes to spare.

As we approached the town, the trails gave way to road that we’d previously covered some two days ago. It was all mercifully down hill at a gentle gradient that made running if not easy, then at least productive.

My American friend then commented that we’d seen the sun rise three times on the same run. At Hardrock you only see two.

We’d been running – or at least moving – for nearly 50 hours. It was certainly the longest continuous run I’d ever done. Three sunrises – that’s something pretty wild.

The streets of Bansko were quiet that Monday morning.

The finish line was quieter still and very low key. Just a couple of volunteers.

We had no idea how many people had finished or how many were still behind us.

We eagerly quizzed the volunteers.

111 were signed up for the race.

23 runners Did Not Start

87 runners started

36 finished – of which we were the final two.

That’s a 43% finisher rate – maybe higher than normal due to the exceptional weather. We were dead last. Just 13 minutes before cut off.

In some ways it felt a comfortable margin. In other’s unbelievably tight.

As me and the American were chatting and laughing and reliving our race – one solitary runner crossed the finish line three minutes after the cut off. He slumped onto the bench and assumed the 1000 yard stare.

Our bonhomie at odds with his broken look. He’d gone all that way – and not finished. Just like I had those two months ago.

I’d got my Hardrock qualifier – just.

In that moment I wasn’t quite sure I’d be entering the Hardrock lottery.

All I wanted now was to be back at my hotel. To shower, eat breakfast and sleep. In an order I wasn’t quite sure about.

***

I showered, ate and slept.

I will, of course, be entering the Hardrock lottery again.

After you’ve done the briefing, and your instructor has done the paper work, and you’ve done the walk-around, they take off.

After you’ve done the briefing, and your instructor has done the paper work, and you’ve done the walk-around, they take off.

was almost like my hands had a mind of their own as we got closer to the ground I had to fight the urge for my hands to want to pull the yoke back towards me – sending the plane back up into the air.

was almost like my hands had a mind of their own as we got closer to the ground I had to fight the urge for my hands to want to pull the yoke back towards me – sending the plane back up into the air. I really felt like I had no idea what my limbs were doing, It was hugely unsatisfying to keep getting it so wrong. It was like someone was pulling the runway out from under me like people do with a tablecloth on fully laid table. Only this time it felt like the planes were just about to crash to the floor.

I really felt like I had no idea what my limbs were doing, It was hugely unsatisfying to keep getting it so wrong. It was like someone was pulling the runway out from under me like people do with a tablecloth on fully laid table. Only this time it felt like the planes were just about to crash to the floor. The solo itself was pretty uneventful.

The solo itself was pretty uneventful.

“

“

Travel sickness occurs when your eyes and inner ear tell a different story to your brain. If you’re being bounced up and down on an ocean wave or thrown side-to-side on a hairpin road, your brain can’t make sense of the world. It’s normally a quite unpleasant experience.

Travel sickness occurs when your eyes and inner ear tell a different story to your brain. If you’re being bounced up and down on an ocean wave or thrown side-to-side on a hairpin road, your brain can’t make sense of the world. It’s normally a quite unpleasant experience.